We Dig Dinosaurs

Episode 2 | 55m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

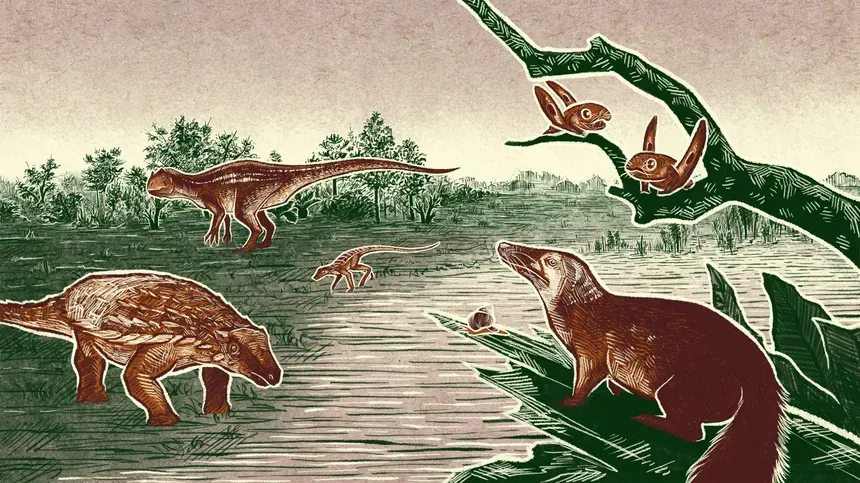

Cruise into the Cretaceous, when astonishing creatures like T. rex dominated the planet.

Cruise with Emily into the Cretaceous, when astonishing creatures like T. rex dominated the planet. But what happened to these tremendous animals? And how did other life forms survive an apocalyptic asteroid crash into Earth 66 million years ago?

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

We Dig Dinosaurs

Episode 2 | 55m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Cruise with Emily into the Cretaceous, when astonishing creatures like T. rex dominated the planet. But what happened to these tremendous animals? And how did other life forms survive an apocalyptic asteroid crash into Earth 66 million years ago?

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Prehistoric Road Trip

Prehistoric Road Trip is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

-Are you ready to investigate?

-I am ready!

-Let's do it.

-I'm Emily Graslie, and I think paleontology is dino-mite.

I've discovered a new species!

As chief curiosity correspondent for the Field Museum in Chicago, I've had the privilege of sharing my deep love of paleontology and the natural world through my YouTube series, "The Brain Scoop."

I'm Emily Graslie!

But I know there's more to discover within our own backyards.

So I've headed back to the area where I grew up in the Northern Great Plains -- the heart of America's fossil country, on an epic road trip to rediscover our planet's past and unearth some clues about its future.

That's profound.

So far on this journey, we've seen how, over billions of years, life evolved from microscopic organisms to towering giants.

And now we're heading into the Cretaceous period, which lasted from around 145 million to 66 million years ago... -All right!

Come on in!

-...and was home to some of the era's most famous predators... -That's a real T. rex contact... -...and their prey.

-This is what you want to find with Triceratops.

-We'll go right up to the final moments of the non-avian dinosaurs, whose reign was ended when a cataclysmic asteroid impact resulted in their extinction.

That asteroid really screwed things up.

So hop in, get your digging tools, and join me on this prehistoric road trip.

♪♪ ♪♪ -My family's from this part of the country, and it's like, where did I go growing up?

I went to Dinosaur Park in Rapid City that was a mile away from my house with, like, giant, life-size cement sculptures of commonly found dinosaurs in the area.

And you'd just take it for granted, 'cause you're like, "Oh, of course.

This is so common in my own backyard.

Everywhere else in the world must just have dinosaurs spilling out of the landscape, right?"

And that's not at all the case.

It's been so much a part of my own personal identity that I didn't even realize until I didn't live here anymore.

♪♪ ♪♪ I'm heading out to visit my dad, a lifelong farmer and rancher who was born and raised outside of Faith, South Dakota.

His dad, my grandfather, had a fascination with the random, mostly incomplete dinosaur bones he would come across while tilling his farm fields.

And that curiosity about ancient worlds is something he passed on to me.

We're out here on the ranch.

We're outside Faith.

Grandpa Graslie was farming and ranching about five miles in that direction.

And was he the first one to realize that there were fossils on his land?

-Well, I think it was common knowledge that there were prehistoric things in this area, but people didn't know what they were or what value they had.

-Like, what was the earliest instance of you hearing about someone around here coming across, like, a big fossil discovery?

-I think probably Sue... -Oh, really?

-...was the first really big discovery here.

-Sue is the most complete Tyrannosaurus rex fossil ever excavated and was discovered just a few miles away from my dad's ranch.

It's named after Sue Hendrickson, who came across it while looking for dinosaurs outside of Faith in the early 1990s.

-And I begin with a bid of $500,000.

-The fossil later went up for auction, where it sold to the Field Museum in Chicago for a record $8.4 million, setting a global precedent for the commercial sale of fossil material.

-She will spend her next birthday, her 70 millionth, at the renowned Field Museum of Natural History.

[ Cheers and applause ] -It also left a huge impact on the local community's impression of paleontology.

Grandpa, who had this lifelong interest in this fossil material -- Do you remember what he said about Sue?

-Yes.

He followed it very closely.

You know, he followed it all the time.

He was very much interested in what would happen to Sue.

He thought it should stay here, as most locals did.

And when it ultimately ended up at the Field Museum in Chicago, he made a special trip up there and took pictures and showed them to everybody about his dinosaur.

-[ Laughs ] Even though it wasn't on his land.

-That's correct.

But we always figured that Sue probably had crossed the fence at least once or twice in her career.

-[ Laughs ] Yeah.

♪♪ We could be standing on top of a T. rex right now.

-Yeah.

We wouldn't know it.

-And we wouldn't even know.

It's kind of fun to think about, though -- 66 million years ago or somewhere in there, there was dinosaurs roaming all over this place.

Getting run down by a T. rex right about now.

-That was their domain then.

There's no way that humans would have been compatible with the habitat that they had.

-No.

We would have been snacks.

-We would have been snacks.

♪♪ -I knew my entire life that my dad's ranch was so close to where they found Sue the T. rex.

And I was always like, "Dad, we got to go look for a T. rex," and he's like, "I don't think that's how that works."

And I was sort of under the impression that you would just, like, take a backhoe and just start digging a hole.

And that's not at all how it works.

♪♪ The discovery of Sue the T. rex helped make this area of western South Dakota famous for its fossils.

But finding them isn't as easy as just grabbing a shovel, picking a spot in your backyard, and starting to dig.

To find a dinosaur, you need to start with land that is already exposed to the elements, like the bank of a river or stream or an exposed bluff.

As the fossil begins to erode out of the ground, rain carries fragments of bone out of the hillside.

Paleontologists look for these fragments, called float, and follow them like a trail of breadcrumbs to try and find the source.

From there, further excavation can begin to see what more of the skeleton may still be in place.

[ Horn honks ] The remains of many remarkable dinosaurs have been found this way.

And I was on my way to meet another.

At the Tate Geological Museum in Casper, Wyoming, my friend J.P. was eager to introduce me to their own exceptional T. rex... What is this?!

-Look at this.

-Oh, my gosh!

-This is our T. rex specimen.

-His name is Lee.

Lee Rex.

-Whoa!

It's a specimen that, unlike the ones you typically see in a museum, tells a very different story.

So, J.P. you don't have the entire thing here, but you have a lot of this dinosaur.

What are we looking at here?

-Okay.

So, what we're looking at here -- Funny you ask.

I happen to have this headless model right here.

-Convenient.

-So this is a model of a T. rex.

It's got one femur, which in life would have been in this position.

The head would be over here if he was complete.

Tail end, of course.

Legs, arms, shoulder blades, et cetera.

The femur has been shifted in this direction.

So here's the femur.

The set of ribs from the left side are laying down right in here, all lined up.

We have 12 of them.

Tucked in between the ribs is a string of vertebrae.

They're a little harder to see.

They come through here to the base of the tail, which goes way over there.

-This is awesome.

Cool.

How do you know this T. rex was out there?

-So, we worked on this ranch in eastern Wyoming with the rancher's blessing.

And we've been working on this place for 14 years now.

-Wow.

-And at some point, yours truly had to get rid of some extra coffee.

So I walked down the hill, found a place that needed watering, and on my way back, I stumbled upon this.

Okay.

It looked nothing like this.

-I was going to say.

Like, "Here it was."

-It was like a little bone, like the piece of vertebra sticking on the surface.

-Yeah.

-And the last two vertebrae were completely out of the rock, as were the chevrons, which are the little bones that hang out under the tailbones.

And those were distinctively T. rex bones.

-At that point you -- -At that point, we were like... -Oh, good!

Oh, yay!

-Happy fossil dance.

-You did a happy dance.

So, is this the final stage for this?

-This is the final stage.

-All right.

I think this is such a nice contrast to seeing the sort of dinosaurs like Sue that are on display, because this is much more indicative of what fossils look like.

-This is what they -- This isn't even how you find them.

If we had left it how you find it, it would've been a rock with some bone sticking out of it.

But this is much more indicative of how it was when it died, when it got buried, and what's left of it.

And so if we had taken this apart to try to make a 3-D mount where they, you know, scare the kids, it would have ended up being a lot of bones borrowed from another specimen.

Then we would've had to point out which ones are ours, and that takes away a lot from it, in this writer's opinion.

-So in this iteration now, leaving it as it is, what are your hopes for how it might be used in education or research?

-A lot of people have come in here and they're pretty impressed.

You can come right up to this thing.

There it is.

We let people touch the end of the femur.

But... -Right here?

-Not any further!

-Right here?

-There you go.

That's a real T. rex contact point right there.

-Wow.

I mean, it feels like electricity, even though I know it's just rock.

But you touch it, and it's like, "Aah!

This thing would've eaten me in a second."

-Oh, yeah.

-I don't think I've ever touched a T. rex before.

That's cool.

-People leave with exactly that.

So whether it's education or just plain thrill... -Yeah.

-They both play along with each other.

So, enjoy the femur.

-No.

Yeah.

Here we go.

Good job, Lee Rex.

It was an honor.

♪♪ Dinosaurs had existed on Earth for more than 160 million years.

But the ones that show up at the end of the Cretaceous period in this part of North America are some of the most famous and best preserved on the planet.

And I'm excited to dig up some of the fantastic creatures that have long inspired the world's fascination with paleontology.

We're heading 400 miles north of Casper, to Hell Creek State Park outside of Jordan, Montana.

It's in this area where the first T. rex was discovered, in 1902 by Barnum Brown, working for the American Museum of Natural History.

Here, we'll be exploring what's known by paleontologists as the Hell Creek, an extensive rock formation spanning four states that preserves the final few million years of the Cretaceous.

The Hell Creek Formation is this place that if you're interested in studying Cretaceous-age dinosaurs, it's just where you go.

It's really productive in terms of the number of species and also the size and the abundance of fossils you can find here.

It takes a long time to get here.

You're driving for hours.

You're driving through a landscape that before you get here is all prairie.

And you're sort of looking around being like, "What are we gonna find out here and what is there to see?"

Until you start to drive into the park and it all opens up in these huge butte formations and these amazing geologic structures, these kind of, like, undulating mountains and badlands.

So it's just visually stunning.

It's beautiful.

But then to know that there's, like, another purpose, like, there's a mission to this -- And this is a place where scientists have been coming for decades and for generations of different paleontologists, looking at all different sort of aspects of this environment.

So coming here and working on my first dino dig of the Cretaceous period -- It's awesome to get that snapshot in a day in the life of a paleontologist out here.

I'm joining a crew of paleontologists from Toronto's Royal Ontario Museum.

Together we're embarking on a mission to recover another Cretaceous-age icon and frequent snack item of the fearsome T. rex -- a Triceratops, which are commonly found in the Hell Creek Formation.

[ Birds chirping ] Last summer, Danielle Dufault was the one to stumble upon part of this Triceratops skull.

We can't know how much more of this animal's skeleton is yet buried underground, aside from what little the crew was able to expose the day before we arrived, which they then covered in this protective layer of plaster.

That's a big jacket.

[ Laughs ] -Triceratops is a surprisingly big animal.

-Wow.

-Can I show you the bit that I found last year?

-Yeah.

-This bump, this is what I saw coming out of the hill.

The hill was going down pretty steep, like this.

And there was just this round bit here.

And what an occipital condyle is, it's the articular piece at the back of the skull, you know, underneath the frill where the first cervical vertebra -- So the first neck vertebra connects to it, and it kind of looks like a trailer hitch.

But it kind of creates a ball- and-socket joint that allows it lots of flexibility for it to move its head.

-Yeah.

♪♪ Walks us back to that date a year ago and how you came to this specimen.

-Well, it was my last day out here and the last day for several of our crew.

We were kind of exploring these hills.

And then from the top here, just the corner of my eye, I come across this perfectly circular and strangely colored bump coming out of the side of the hill.

I did a little dance.

I squeaked a lot.

And then I radioed Dave, and I said, "Dave, it's a Triceratops condyle."

And lo and behold, he confirms it.

-Yeah.

-He says, "Yeah.

That's what it is.

It's a condyle."

So I was like, "Okay.

Here we are.

We've got something to come back for."

We've got a lot more work to do.

Less talking, more digging?

-[ Laughing ] Yeah.

There you go.

[ Indistinct conversations ] -So we still have a lot of the skull to find.

We basically have that very back part of the skull where it joins the body, and we have what looks like most of the neck shield.

But we're still after the horns and the jaws.

[ Indistinct conversations ] For me, this is pretty much living the dream.

-Yeah.

It really is like a treasure hunt.

-It is.

-Except instead of treasure, you're finding ancient, amazing animals that are bigger than elephants.

-That's right.

I mean, it's scientific treasure.

Everything that we know about the history of life all started here in the ground as a single fossil.

We've built up more and more and more fossils, which has helped us piece together the history of life.

And we still have a lot of questions to ask about the history of life, and that's why we're out here.

-It's looking pretty horny.

-Yeah.

It's got a nice curve to it.

-So, um, Emily and Dave, we're gonna do -- He has a bone, I think.

-Oh.

-So we're gonna talk to him quickly.

-I like the looks of that.

♪♪ Well, that's good news.

-[ Laughs ] -Yeah.

This is a bit surprising to me.

Because basically we ended our last year's work, like, probably centimeters from this bone.

And, you know, Ryan' come along, and he's got the lucky draw.

And, you know, this is a substantial bone.

-We're pretty confident this is one of the two brow horns of the Triceratops.

-Wow.

-Just judging by the diameter of it.

Nothing in the skull is this massive.

And these can get up to three feet long.

-Are you serious?

-This is incredible.

I mean, this is bigger than a baseball bat around, longer than a baseball bat probably in total if it's not broken.

I mean, this is a massive horn.

-We're already seeing about a foot of it here.

So, Dave, do you think that this brow horn continues to go down further?

-Yeah.

All the indications are that it's just gonna keep going.

It's got just nice root mat there, which suggests that it's still in its natural position in the rock, going straight down.

I mean, this is what you want to find with Triceratops.

I mean, this is part of its name.

-Right.

Yeah.

That's exciting.

-Way to go.

-Nice work.

♪♪ -We found the most important part of our Triceratops... -Oh, yeah?

-...in the last 20 minutes here.

This is the nose horn.

And we can use the nose horn to tell what species of Triceratops that we have.

-Oh, really?

-We have a pretty long nose horn.

So this is characteristic of the species Triceratops prorsus.

-And you can learn all of that just by this small amount that's exposed here.

-Yeah.

-Whoa!

-It's like the fingerprint of this type of dinosaur.

-If we have our little guy here, our little reference, this skull is kind of upside down like this.

-Yeah.

That's right.

-And this right here is this nose horn?

-That's right.

And then Ryan's horn just around the side here might actually be connected to this part underneath the frill.

-Wow.

-So it's a little bit mashed around but basically with this, the entire skull is here.

-That's amazing.

Were you expecting to find this today?

-I w-- No.

-[ Laughs ] -I was hoping we would find it.

And to be able to find two of the three horns in the first few hours of today with you visiting is pretty amazing.

-Yeah.

-Ah!

So good.

♪♪ -Oh, my God.

It's all there.

-Your paintbrush is just up to your right.

If you want to give it a brush.

It's just right there.

-That's nuts.

-Yeah.

You're almost there.

Yep.

Keep going.

You're almost there.

Keep following that edge.

The front of the face.

Yeah.

That should be about it in there.

Clear it out.

One more.

Yeah.

Take that little piece off right there.

Yep.

And now give that a brush, and that's pretty much the very tip of the beak right there.

-Oh, my God.

That's amazing.

-It is amazing.

Not bad for our first Triceratops.

-That's just wild.

I'm a little emotional right now.

-Oh.

Me too.

-[ Laughs ] -Yeah.

-Me too.

-Oh, that's awesome.

-I could have never imagined it was gonna look this good.

-Yeah.

I'm pretty happy.

-This is amazing.

This is really cool.

Aah!

I'm freaking out.

-I just can't believe that this all happened on the day that you were here.

-I know.

[ Laughs ] -So, what you just exposed is the very tip of the beak of this Triceratops.

And horned dinosaurs have this special bone called the rostral bone.

And in Triceratops, when they get big, it just fuses right onto the front of the face, and it's got all these blood vessels and holes in it that support a big keratinous sheath over that.

So just like a sea turtle or a bird, it would use that beak to crop plants, move them back into its mouth, where it would slice and dice them with its battery of teeth.

-Wow.

What an amazing animal.

-It is an amazing animal.

-And this is so beautiful.

I can't believe it's all still together.

It's perfect.

[ Indistinct conversations ] This has turned out to be a pretty amazing day.

-Today has been the pinnacle of this so far.

This is only day three, and we've already uncovered so much more than we could have expected.

-What does it feel like to have been the one to discover an animal that went extinct some 66 million years ago?

-Oh.

-And for you to be the first person to see it ever?

-It's a little bit hard to fathom.

-Yeah.

-It is.

You know, this is an animal that was living its life here.

And my favorite thing about this is that this is something that someone can learn from.

Maybe it'll be of importance to somebody's studies, and to me, that feels really good.

I'm excited about that.

-I think we really lucked out with the Triceratops site in that it was like best-case scenario, where last year that came out, they prospected, they saw a little bit of the back of the skull.

But you have no idea what's gonna be buried underneath.

And so you're kind of -- You have your hopes up, but you don't want to get too excited.

Until we started digging into this thing and revealed one of the brow horns and the nose horn and then the front of the snout.

That is an amazing thing to be a part of, to have this skull that is identifiable.

It has these characteristics that you can tell that it's a Triceratops.

So that's like, to me, a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

I got to be a part of that.

♪♪ We're traveling further down, to southeast Montana, where a crew from the Museum of the Rockies is excavating bones from a different species of Triceratops.

Because rock layers in the Hell Creek Formation preserve a few million years of time, paleontologists like Dr. John Scannella are able to study two different species of Triceratops and see how, over time, one evolved into the other.

-We're in the lower part of the Hell Creek Formation.

And so what we discovered a few years ago is that if you're in different stratigraphic layers of the Hell Creek, Triceratops actually changes through time.

So the lower part of the Hell Creek, what you have is Triceratops horridus, and then as you go up through time, near the top of the formation, you find Triceratops prorsus which has a longer nasal horn and kind of a shorter beak.

-How are you certain that these are actually different species of dinosaurs and not just different ages or found in a different part of the formation?

-Well, we have such a large sample of examples of Triceratops that we can see how Triceratops -- how its skull changed as it grew from a baby to an adult.

So we know what a little Triceratops looks like and a bigger Triceratops.

And the differences we see between the two species of Triceratops are outside of that range of variation throughout growth, and they do not overlap in time.

So you won't find a Triceratops horridus right next to a Triceratops prorsus.

You just find prorsus when you're high up in the formation and horridus lower down.

[ Horn honks ] -Back at the museum in Bozeman, these Triceratops fossils are added to a collection of hundreds of others.

They can be used for comparative research once the bones are removed from the rock matrix that has encased them for tens of millions of years, a delicate process that can take thousands of hours.

-It wasn't until relatively recently that paleontologists got their first good look at what a little Triceratops skull looks like.

And so it's been discovered that as Triceratops grew up from a baby to an adult, its skull transformed.

-Wow.

-It totally changed shape.

Like the horns of a little Triceratops curved backwards, and then as they get older, they go forwards.

And little Triceratops have these little spikes around the frill called epiossifications.

They start off really triangular and spiky, but then as Triceratops gets older, they flatten onto the edge of the frill.

So we're learning a lot about how Triceratops grew, in part because there are so many specimens of Triceratops to study.

-So, is this sort of the reason why you continue to go out and collect more material?

Because someone might look at, you know, 100 Triceratops and be like, "Well, we got enough.

We don't need any more."

But that's not why you collect them.

-Right.

I mean, the more specimens we have, the more we can learn about variation in a dinosaur like Triceratops.

So two different dimensions of change, like growth changes and then evolutionary changes, which is really cool to be able to see.

-How are you able to study growth in an animal that's been extinct for that long?

-One of the things you can do is if you have multiple examples of an animal like Triceratops, you can actually look inside their bones through the process of paleohistology, where slices of bone are taken out and then ground down until they're so thin that light will pass through them, and then can study their microstructure.

And then you can see this one is relatively more mature than that one, and this one's the oldest of these three and so on.

♪♪ -So what you see here in tan and brown is the actual bone material preserved and slightly stained by whatever minerals were in the soil.

And then the open white spaces are the vascular canals where the blood supply would have actually traveled through while the animal was alive.

♪♪ -Do you ever get tired of studying Triceratops or finding them?

-No.

Whenever you find a new Triceratops, it's like meeting a new friend.

It's like, "Oh, hi."

-Yeah!

That's a really great way of thinking about it, because they are so individual, and every new one that you find can lend itself to a whole new suite of discoveries that enhances and builds off this research that you've been doing for years.

That's exciting.

How many Triceratops are in this collection?

-Oh, God.

Literally hundreds.

Those are all Triceratops.

Yeah.

So that's more of the prepped Triceratops area versus these are either too oversized or have been prepped.

-I think a lot of times we think of big scientific discoveries happening in isolation, in giant labs in huge universities in major cities in the country.

And a lot of people might not think of a place like Bozeman, Montana, as being in the heart of amazing paleo research and science.

-Yes, and cutting-edge research -- no meaning to go into a pun there with histology work.

But it's also very, very true that we do have this great research team here that you might now expect in a smaller town like Bozeman, Montana.

We do estimate that we probably have about 5% to 10% of our fossil collection upstairs on display.

-And are they actually fossils or are they models of fossils that are then housed down here?

-We like to have a combination of actual fossil, because your average visitor may never have seen a fossil before in their entire life.

They've never necessarily seen something that's 200 million years old or 66 million years old.

I think it's a very neat thing that when you go upstairs and look at Montana's T. rex, that mount is over 60% actual fossil.

-Wow.

-Yeah.

I think that's really neat for kids and families to be able to say, "That's the real thing."

And then they think it's gonna come alive like "Night at the Museum"... -[ Gasps, screams ] [ Dramatic music plays ] -I'm like, "No.

It's not that real."

But we house the most Tyrannosaurus rex fossils in the entire world, and we house the most Triceratops fossils in the entire world here at Museum of the Rockies.

♪♪ -Many exposures of the Hell Creek Formation have been explored throughout the history of paleontology in the American West.

But there are still vast areas where the formation is not yet well surveyed.

The Standing Rock Sioux Reservation is in the heart of this fossil-rich region and just starting out with their own paleontology program.

In 2007, the tribe became the first in the nation to enact an official fossil-management code and established the Standing Rock Institute of Natural History to document, excavate, and study the fossil material found on their land.

Yeah.

It's still pretty damp out here.

Ben Eagle, the institute's fossil preparator, is taking us out to one of the tribe's known Hell Creek exposures.

We had to be careful to not reveal the exact location out of concern that someone might remove the fossils illegally and without knowledge from the tribe.

So just all along this ridge here, you have stuff... -Pretty much, yeah.

-...weathering out.

-Do you know what bones they belong to?

What animal?

-Yeah.

It's most likely going to be Edmontosaurus.

-Okay.

-And a lot of mixture of other creatures.

-Is this the Edmontosaurus site you were telling us about?

-No.

No, no.

-Oh, this is just nothing, then.

What is this?

There's just... -Fragments.

-...explode-a-bone everywhere.

-Fragments.

Fragments.

Most of our therapods teeth came from this one site.

-There is so much material here.

It's like the hillside is just, like, weeping with fossil fragments.

-We walked probably like three feet.

-Yeah.

-[ Chuckles ] This is an Edmontosaurus root of a tooth.

-Wow.

So when you look at the side of an Edmontosaurus jaw and it has all those little peg parts, that is what is below the gum line.

-Yeah.

We only see that little shed part.

-Wow.

Do you find a lot of these out here?

-This is actually unique.

I've only seen these roots in this one site so far.

Really big one too.

-That's amazing.

Look at all this stuff.

It's just coming out of the hillside.

I have no idea what that is.

-You're probably standing on a T. rex tooth or something.

It's really hard to step anywhere without stepping on a fossil.

-I could just spend hours in one tiny square foot of this area and probably find more things than we would have spent days looking for somewhere else.

-Yeah.

We find so many Edmontosaurus teeth, I kind of stopped collecting them.

Otherwise I'd be here all day.

-Yeah.

How many paleontologists have you brought back here to look at this material?

-Just two.

-Just two?

[ Laughs ] And have they done any, like, active excavations or trying to, like, dig back into the hillside at all?

-No.

This is -- Did some research on it, but so far just looked for one day and headed out.

-Whoa.

Are you concerned about people finding out about this site and showing up?

-Oh, yeah.

I mean, a lot of our really good stuff came from this one spot.

-Yeah.

-Yeah, it's kind of way in the middle of nowhere.

That's pretty much its only protection right now.

Don't show too many people here.

Plus, do you think you could find your way back?

-Oh, no.

If you took off without us, we would be lost.

We'd be dead.

I would become one with the fossil bones.

-Yeah.

Yep.

This is just one tiny little section here.

We got a huge area.

-We're walking around this bluff, and we're seeing entire bones eroding out of this formation.

This is the kind of material that some of the people who we'd been filming with before probably would've stopped and jacketed this and documented all -- And it's just here.

And he's like, "No, we're not even there yet."

Like...this place is wild!

I don't know what that is, but somebody does.

[ Indistinct conversation ] There's a what?

-We think we found a skull coming out of the thing.

-So, like, this is where the root would have been, and it lost that part.

But you can still see this perfect tricuspid crown.

What is happening right now?

Where are we?

This place is blowing my mind.

You can see the little marrow inside.

The level of preservation on this material is absolutely outstanding.

There's just the whole limb bone.

Just an entire identifiable limb bone.

Not just, like, little scrappy pieces.

Whole articulated, in situ, in the rock, weathering out of this iron concretion.

Hanging out.

Did you know this was here?

Of course.

Ben is, like, playing it cool.

-And for now, since I don't really have the time or manpower I got just to cover it in Vinac and hope it's still there next year.

-Yeah.

Just put some glue on it as like a bandage to hold it together and keep an eye on it.

-Yeah.

It's just time and resources.

We have so much here.

It's hard to keep up.

-When it's just you.

-Yeah.

-You're the only person.

I feel like we have had a lot of privilege being invited to a lot of digs all over this part of the country.

This would blow the socks off most of the paleontologists that I know.

-Yeah.

Standing Rock is just starting out.

I mean, seven years of collecting, 12,000 fossils.

We've got some very unique sites and just a lot of potential.

-Thank you for taking us here.

This place is awesome.

-Yeah.

-I'm a little speechless.

Like Ben said, the potential for new discoveries here is high, and it's exciting to think about what new insights he and the Standing Rock Institute have yet to make.

♪♪ If late Cretaceous dinosaur fossils are found here, what other aspects of their environment might also be preserved?

You have these dinosaurs that capture the public's imagination, and they're really sort of a gateway for people to become interested in paleontology.

But at the same time, there is this really compelling other side of the story.

And then you start to dig a little bit deeper -- no pun intended -- and find these other facets of paleontology that open up this Cretaceous world in a way that a single dinosaur might not be able to do.

Many sites in the Hell Creek Formation preserve more than just the dinosaurs that called this area home.

Our next stop in western North Dakota produces an astounding variety of fossils from the animals that lived alongside their more familiar neighbors 66 million years ago.

-Here we see right here there's a little piece of skin armor.

That's our crocodile evidence from this site.

There's also just some additional bone fragments from some of our dinosaurs.

A little bit of turtle here as well.

-North Dakota State paleontologist Dr. Clint Boyd has been taking a close look at these smaller, but oftentimes more significant details of the environment at the end of the Cretaceous period.

-Dinosaurs are just one part of the story.

And if we see a similar pattern across all of our different types of animals and plants, then that gives us a fuller picture of what's happening.

-But perhaps one of the most stunning things that can be found in this particular area is what paleontologists refer to as the Cretaceous-Paleogene, or K-Pg, boundary.

It's a geologic record of the day the dinosaurs died.

-So we are looking at the actual K-Pg boundary.

So this is the moment of extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs -This sort of reddish-orange clay layer right here?

-Correct.

-So you can find dinosaurs anywhere in the world below this boundary line, if you're looking at this sort of in a stratigraphic column, but not above it.

-Not above it.

Never -- At least not yet.

If someone gets really lucky, maybe someday.

But so far, no.

It's a great little spot to kind of think about if you spread your hand out.

You know, you can put your thumb below that boundary and then up where your pointer finger is at, there's no more dinosaurs.

So dinosaurs to no dinosaurs right across that little spot.

-Dinos.

Asteroid impact.

Really bad day.

No dinos.

How was this boundary even discovered and how was it linked to this mass extinction event?

-Oh, well, it was a lot of hard work by people doing a lot of stratigraphic work and then looking at the sediment under microscopes they found the iridium spike, which, iridium is something that's not too common on Earth.

but is more common in objects outside Earth and the solar system, like asteroids and meteorites.

So all of that evidence just kind of started coming together to point to there was some event right here.

And you tie that to the fossil evidence of, like I said, not just the dinosaurs going extinct, but so many different types of plants and animals going extinct at this time.

It just all kind of works together.

-So it's amazing that we can be here in North Dakota and you've got an amazing fossil record preserved below this boundary.

But then you can come back to the same place and compare how things changed above and below this.

-Right, and that's part of the benefit of the underlying rocks the Hell Creek Formation being so productive is that we can say, for pretty certain, that the fact that there's no dinosaurs above isn't just because they weren't preserved based on our preservation below and that abrupt change from dinosaurs to no dinosaurs.

It's really good evidence that this is the actual moment of the loss of the dinosaurs.

-This is a pretty amazing thing.

I guess if you get up really close with your face next to it it might not look like much.

It might not be the most visually striking moment in geologic history.

But just to know that this line represents such a catastrophic moment on Earth.

That geologists know this one in particular and know what its significance is, you know, coming to see it is kind of an intimidating moment.

But at the same time, you know, the dinosaurs had they not gone extinct, we might not be here.

The world would be a very different place today.

And so it's really a humbling experience to think about everything that has transpired in the last 66 million years since the dinosaurs have been wiped out.

And so it is just this moment of reflection, like "Oh, I wonder how many other seven-mile-long asteroids are heading our way."

That's not terrifying at all.

♪♪ ♪♪ Did this extinction event just happen in a single day?

-Well, that first day of the impact would've been very bad.

There'd have been tsunamis everywhere.

People have proposed maybe global wildfires across the planet from all the ejected material coming back down.

But the effects would have been significant on a days, months, weeks, maybe in years time scale.

The asteroid impact hit in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico.

It's a platform of both carbonate and sulfate rocks.

And when you vaporize large amounts of carbonate and sulfate rocks, you put a large amount of carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide into the air.

The sulfur dioxide will eventually convert into acid rain and create significant acidification.

Perhaps most importantly, though, is all of the physical ejecta that gets up in the atmosphere, little tiny dust and soot particles.

And they're gonna actually block out the sun on the order of maybe a year or two.

And actually, the sulfur dioxide particles will form aerosols that'll also help block out the sun.

And so what's been proposed is that you're blocking out the sun for a couple of years and you're destroying basically the base of your ecosystem, right?

You're basically stopping a lot of plants from -- They might be able to survive in seed form or something, but they're not going to be a source of food to the rest of the ecosystem.

And that can lead to ecosystem collapse.

-So if you happened to survive the asteroid impact, the day, you might have been wiped out by acid rain, a wildfire, or if you survived all of that, your food is gonna be depleted 'cause the plants can't get the sun 'cause the sun's block-- It sounds horrible.

It's amazing that anything survived at all.

What a terrible day.

Everyone's having a hard time.

♪♪ -My name's Tom Tobin.

I'm an assistant professor at the University of Alabama in the department of geological sciences.

My primary area that I work is as a geochemist.

I combine that with invertebrate paleontologists, so I work with a lot of invertebrate fossils, like clams, snails, but also extinct ones like ammonites.

There's a lot of debate in our community right now about whether other potential contributing factors affected the extinction or if the asteroid's the only thing that matters.

So a lot of my research out here is focused on trying to reconstruct the temperature records before, during, and after the extinction, through the Cretaceous and the Paleogene, to see how the climate changed across these intervals.

Shiny things.

And I'm interested in this from the perspective of does anything else contribute to this extinction and if so, how?

-To help answer this question, we're on the hunt for some unexpected witnesses who can testify to the abrupt change of their environment during this impact event.

-Do you want to start digging?

-The small and mighty clam.

Oops.

♪♪ -Broke this one a little bit, but... ♪♪ -Oh.

[ Exhales sharply, laughs ] So, Tom, out of all of the things you could study in the Cretaceous -- you know, the big dinosaurs -- why focus on clams?

-Clams provide us a variety of things.

Actually, I like all mollusks because they do a couple things.

They put down a calcium-carbonate skeleton.

There's a formula that relates temperature, the oxygen-isotope ratio of the shell, and the oxygen-isotope ratio of the water the shell was living in.

And we can geochemically analyze the shells and say, "What was the temperature like for these shells as they were living?"

The other thing they do is they grow by accretion.

So they create this record through their life span.

And there are lots of them.

As you can see, there's shell hash everywhere.

-So because of the chemical that their shells are made out of and because these animals put down new layers year after year, you can actually look at the layers of their shell and figure out what the temperature was like millions of years ago?

-Yeah.

These will give a way of saying, "This is what the environment these dinosaurs were roaming around in."

We'll kind of wander this way, maybe look down in the valley a little bit, see if any good stuff has rolled down.

And yeah, we'll go from there.

-Okay.

-Cool.

-Happy clamming.

-Let's go.

-Happy clamming to you.

♪♪ ♪♪ -Yeah, yeah, yeah.

-[ Laughs ] Did you find something good?

-Yeah.

This is a really good one.

This is the biggest one that I've seen.

Should I just leave it in place?

-I will come investigate.

It almost looks like it's two of them together.

-Oh, yeah.

It probably is.

That's what we really want to find.

-That's another good one too.

I was going for that one next.

-Sorry.

-[ Laughs ] -You invite me over to your spot, I'm gonna poach all your good stuff.

-This is awesome.

Oh, here's another big one together.

In here.

I love clams.

-So yeah.

We'll take a look at that one.

-Cool.

-Sweet.

Can you wrap this one up, too?

♪♪ -The clam dance.

No, this is the clam dance, 'cause they're like a bivalve.

I'm done.

Clams are so underrated.

-They are underrated.

[ Birds squawking ] -Morning.

-Howdy.

-Howdy.

I'm up!

I'm awake!

-There's been a group out here that's focused on understanding the paleontology across the end-Cretaceous mass extinction and to try and understand what happened to the dinosaurs and their friends and what recovered, what took their place.

-Oh, there it goes.

Huh.

-Some sort of weird stem thing in there.

-Huh.

-That's interesting.

I don't quite know what that is.

That's actually -- It's odd enough, I think I'd like to collect that.

-Oh, cool.

-Kind of weird.

Yeah.

My name is Paige Wilson, and I'm a graduate student at the University of Washington.

And I'm a paleobotanist, so I study fossil plants.

When I first became interested in paleo, I really was interested in sort of looking at big ecosystems and understanding what was happening across the landscape through time.

Plants are such a reflection of the environment in which they grow, and they're such a foundational part of every ecosystem.

So you can probably maybe already get a sense that this is a very not-diverse site.

Almost all of what we see here are these palmate, so they have multiple primaries.

I think we've only found maybe like two pinnate leaves, with a single midvein.

So just in terms of a very gross generalization of the morphology of the leaves here, they basically are almost all from a single taxa or species, I think.

-That is wild.

There's no diversity, then.

-Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

Almost no diversity here.

While most of the taxa and species that were present here were around in the Cretaceous, there are a lot of species that were present in the Cretaceous that we just don't find anywhere in these sites above.

So we're finding that there definitely was a mass extinction among plants.

-That asteroid really screwed things up for a lot of different species.

-Yeah.

Yeah.

For sure.

-I want to find more plants.

Let's go!

-I think the K-T boundary and K-T mass extinction are really, really important for us to understand.

It not only radically changed what the earth looks like, but also set up the modern ecosystems that we see around us today.

And so really important for us to understand not just what our earth looked like in the past but also what it might look like in the future.

-Let's get this big chunk out.

-That's a nice one.

Do you want to try chipping it, see if anything's on the inside?

-Yeah.

Oh, there's, like, a leaf that popped out the bottom.

Ooh.

You get good margin with that.

-Yeah.

-Is this worth keeping?

-I think so.

Um, and I think that one's gonna be the last one.

-Okay.

Oh, yeah.

I collected this one too.

That's nice margin.

-I think you found all the best ones today.

Excellent, excellent work.

-This is cool!

Fossils are cool.

I love that there are so many different things that they can find out here.

You know, it's not just like one group or one scientist or one university.

There are scientists from all over the country, internationally that are coming here.

They're all working on different things.

And then at the end of the day, they all get together and camp and talk about what they found and kind of rehash the day and bounce ideas off one another and then go back out the next day.

You know, it doesn't feel like work out here.

It feels like we've just been having a good time.

♪♪ Other groundbreaking research into how life recovered after the asteroid impact continues in the tiny town of Bowman, North Dakota, at the Pioneer Trails Regional Museum.

This museum was started by a group of local hobbyists to provide the community with a space to share their interests with tourists.

But just because this work is done by nonprofessionals doesn't mean their research isn't rigorous.

Lifelong paleo-enthusiast Dean Pearson volunteers his time sorting through the tiny clues left by everything from fish to mammals and the other small and mighty survivors of the extinction event.

-This sediment that I've got in front of me represents from the point of the formation contact through the KT boundary, which is the point of the extinction of dinosaurs, up to about two and half to two and three-quarters meters above the point of extinction.

So it basically contains small, lower-vertebrate material that represents the recovery floor after the extinction of the dinosaur.

And each of these vials contains... -Wow.

-...bits and pieces of small vertebrates.

And the only way to find these are to bring home the sand or the matrix muds that it comes in, wash it under a screen.

And so we basically made a stratigraphic column, which is a slice through time in the sediment that was one meter square, divided that into four quadrants -- into basically a northwest, northeast, southwest, southeast quadrant.

And then we sampled that five centimeters at a time as we washed this -- for 285 centimeters.

-Oh, my God.

[ Both laugh ] That's amazing.

-So we washed approximately 5,000 kilograms to end up with about 2,500 specimens.

Then we picked through that under a microscope to find out what's there.

And then we go into a more powerful microscope to actually take a look and see if we can identify the specimen that we found.

-When you're comparing those level of microfossils that you have after the event to those that were collected before the event, how does life change?

-Well, life changes in the sense of a lot of the mammals that existed at the time of the dinosaur don't exist today.

And you can see that there's been changes in the fish.

So the environment did change, but it didn't change in the sense of not having a capacity to maintain life.

-Do you see life recovering quickly after this extinction event?

-Well, what we're seeing here is the possibility that it didn't last as long, that there were things that appeared immediately.

Some things appear later on but not significantly later on to mean that it probably was tens of thousands of years rather than hundreds of thousands of years before the recovery.

But, I mean, to me, that's the real important part about this, is that it's got a really unique story to tell that no one's ever looked at before.

-That's so cool that you have this extinction event in your backyard, you can go out there, take these huge samples, take the amount of time to sort them, and then make these resources available to other scientists.

I would not have the patience for this.

-Well, a lot of our volunteers didn't either.

[ Laughs ] -[ Laughs ] Really?

It has been incredible to see how that asteroid irreversibly impacted our planet and to learn more about how life, in so many different forms, was able to recover in the thousands to millions of years that followed.

Understanding biodiversity's resilience and adaptations through time is a huge part of the story of how we got to where we are today.

♪♪ After so many visits to museums and field sites, I was ready to take a moment and enjoy the local scene.

And lucky for me, I was in the perfect place for it.

Every summer, paleontologists break from their research and come together in the town of Ekalaka.

Here, the Carter County Museum hosts an annual weekend event, the Dino Shindig, which brings the locals together with visiting scientists in celebration of the region's rich fossil history.

I'm excited to see some of the friends we've met along our road trip so far and kick it back with them Montana style.

♪♪ We are here at the pitchfork fondue, which is like a kickoff event for the Dino Shindig here in Ekalaka, Montana.

This is amazing to me that you have all these community members, these scientists from all around the United States, all coming together, putting giant steaks on pitchforks, dipping them into a vat of oil, and having a good time.

Talking science.

And also fried meat.

What more could you want?

I've never eaten a steak that was stabbed on a pitchfork and thrust into a massive vat of oil.

That's really good.

-[ Laughs ] -That is really good.

♪♪ It's a great way to celebrate the community's involvement with the paleontologists who rely on these partnerships to further their research.

♪♪ -All right.

So, we're gonna get started with the Robo Rex.

One, two... three!

[ Children screaming ] -The Shindig kicks off after the pitchfork fondue, and everyone from the locals to out-of-town visitors come together for dino-themed activities, family-friendly games, and talks from visiting scientists.

Personally, I'm here for the cool face painting.

-Okay.

I think you're good.

[ Laughs ] -Aah.

-Ready?

Oh.

Let me... -[ Laughing ] Oh, that's awesome.

Yes!

Rawr, rawr, rawr.

This is amazing.

-The big thing with the Shindig was to make sure that all these discoveries that are happening around Ekalaka actually come back and people get to hear about them and learn where their dinosaurs went, learn what they've been hearing about, what science is being done with their dinosaurs and from all these different landowners' lands.

So it was a big science-communication thing with the community, not just another paleo conference.

♪♪ -Super excited you guys are all here.

Thank you for participating in the seventh annual Shindig.

Congratulations, all.

You made it here.

-On the final day of the Dino Shindig, the museum's curator, Nate Carroll, takes a group of Shindiggers out to a local's ranch so they can experience the thrill of prospecting for fossils on their own.

-We get to take 60, 50-some people into the field.

So these are a bunch of folks that have come from Florida and Minnesota and who are dino enthusiasts.

But that's a bone.

-This is a bone?

-You bet.

We really have an amazing fossil resource that folks will drive a long ways just to participate in the experience.

-I found a theropod leg bone.

[ Buzzer sounding ] Or an arm bone.

A limb bone?

Humerus.

[ Bell chimes ] Wing.

Chicken wing.

I found an ancient chicken wing.

That's really exciting.

And then -- So, Shindig 2019, therapod humerus.

E. Graslie.

'Cause I found it.

I'm riding the wave of scientific discovery right now, and it's taking me to the shoreline of Cool Town.

[ Laughing ] This is awesome.

♪♪ -All right.

We're all here.

Let's take a group photo.

-It's become apparent to me that paleontology is a field that's heavily reliant on the sense of community.

Relationships between landowners, scientists, amateur collectors, and enthusiasts are built over years, sometimes even decades.

The sun is setting on our adventure through the Cretaceous.

But we still have tens of millions of years to go.

Our ancient world begins to come into sharper focus as we drive closer to the present day.

The fossil record will reveal how our planet reshaped itself in times of great acceleration and change -- stories which today contain messages about the future for all of us.

-Next time on "Prehistoric Road Trip"... Wow.

-We get the first dogs here.

-The first dogs?

Everyone must be so happy about this.

-Every day I come in.

I go, "This is so cool."

-This is the strangest-looking thing.

-Got to find that pallid.

Oh, geez.

Aah!

[ Laughs ] My first thought was, "I'm really glad I got a stair stepper."

I just got goose bumps.

-[ Laughs ] -I can't remember the last time I had this much fun.

Am I wrong?

-Whoo-hoo!

-I just ate a bug.

Ugh.

Aah.

There it is.

Sorry, buddy.

Whoo-hoo.

What sound a deer makes?

-[ Grunts ] -Yeah.

Kind of like a... -That's pretty good.

-Like, "Waah."

-To order "Prehistoric Road Trip" on DVD, visit Shop PBS or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

This program is also available on Amazon Prime Video.

Episode 2 Preview | We Dig Dinosaurs

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: Ep2 | 30s | Cruise into the Cretaceous, when astonishing creatures like T. rex dominated the planet. (30s)

How the Soil Tells the Story of the Dinosaur Extinction

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep2 | 3m 18s | The soil in North Dakota has clues from the day the dinosaurs went extinct. (3m 18s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by: